by Jessie Lynn McMains

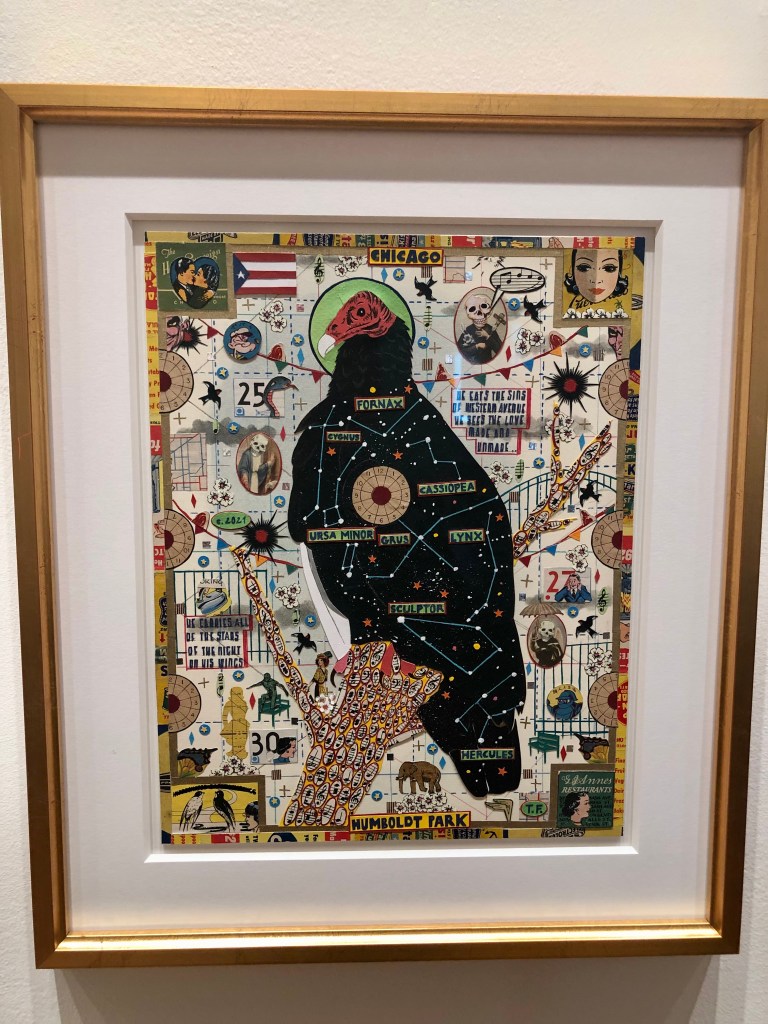

All of Tony Fitzpatrick’s collages—from the largest to the smallest—are packed full. Each one is a visual list, a bright litany, of his loves and inspirations. In interviews and on his website, he mentions some of them: comics (two of his earliest influences were Dick Tracey and Mad Magazine), religious art (such as the holy cards he grew up with in Catholic school), cities he has traveled to, children’s books, tattoo designs, folk art, and music. The predominant images in his works are often monsters, moths, women, retro business signage, or birds, but when you look, really look, at one of his collages, you will notice so many tiny, significant details. There are lines of poetry, musical notes, unfilled squares from crossword puzzles, bits of maps. There are vintage matchbooks and cigar bands. There are flowers, angels, gangsters, trains. Look closer. There—a small sketch of a building—Myopic Books, maybe, or Jerry’s Red Hots. There. That showgirl has a tentacle springing from her head. Jesus’ eyes are glowing green. There are skulls blooming from the center of that flower. That vulture wears constellations on its wings. The images in his collages are like milagros pinned to an altar, charms on a necklace worn by a moth-winged woman with a dress made from flowers and skulls.

I entered the Cleve Carney Museum of Art to see Fitzpatrick’s final museum show—Jesus of Western Avenue—and was immediately overwhelmed. Overcome. Hundreds of images jumped out at me: the signage of drugstores, used car lots, and jazz clubs. Pot-smoking mermaids with lemon-yellow hair. Women made of fog standing in the rain, monstrous reptiles, science fiction monsters weeping oily black tears. And birds, birds, birds— a dazzling aviary of strange angels that, though they are drawn and collaged and kept under glass, gave me the feeling that at any moment, they might take flight, or sing.

In the spring of 2020, when the world shut down, Fitzpatrick took refuge in the 207 acres of prairie and lagoon near his home and studio in Humboldt Park. Over the course of a year and a half, he created nearly twenty pieces portraying some of the birds he witnessed during that time, which came together as The Apostles of Humboldt Park. His apostles are owls and woodpeckers, goldfinches and green herons, dark-eyed juncos and northern flickers, and many others.

Still others are birds that would never be seen in Chicago under normal circumstances. “The Plague Angel” features a Dracula parrot (also known as Pesquet’s parrot), which is native to New Guinea.

Though these birds do not naturally live in the area, I can picture one there, a fierce, black-eyed, blood-red-bellied thing, perched in a skeletal winter tree in Humboldt Park, like a bad omen, or a blessing. By placing one in Chicago, even if only in collage form, Fitzpatrick has added them to the mythology of the city. I think of what Aleksandar Hemon wrote in “Reasons Why I Do Not Wish to Leave Chicago: An Incomplete, Random List:” The Hyde Park parakeets, miraculously surviving brutal winters, a colorful example of life that adamantly refuses to perish, of the kind of instinct that has made Chicago harsh and great. I actually have never seen one: the possibility that they are made up makes the whole thing even better.

Though Tony Fitzpatrick’s artwork is inspired by many different places—in the pieces featured in Jesus of Western Avenue alone, I spotted Paris, Florence, Juarez, and Ocean City, Maryland—it always comes back to Chicago. Chicago is not only his home; he has become synonymous with the city. In 2009, the Chicago alt-weekly Newcity named Fitzpatrick the “Best iconic Chicago personality now that Studs (Terkel) is gone.” In an episode of Fear No ART Chicago circa 2011, the host Elysabeth Alfano says to him that she’s never sure if he’s going to “write her a poem or drop the f-bomb,” which could just as easily describe Chicago’s personality. And at one time in his life, he was a semi-professional boxer, a perfect fit for the “stormy, husky, brawling” City of the Big Shoulders.

Fitzpatrick is something of an underdog, or at least an outsider. He’s both well-established and somewhat unknown. His art first received major notice in the 1980s. He’s done book and album artwork for the likes of The Neville Brothers, Steve Earle, and Lou Reed, among others. Aside from being a visual artist, he is also a poet, playwright, and actor. Still, when I tell people he’s one of my top-five favorite contemporary artists, most have never heard of him. I don’t think he would mind this; this career on the (relative) margins. Fitzpatrick champions the underdogs. He has stated that Jesus of Western Avenue will be his final museum show. “I think it’s time for people who look like me to get out of the way, and create some institutional wall space for people who have not had a light shined on them,” he says. In an essay for the Poetry Foundation, he writes about the first time he heard Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side:” it…reached into the white-bread heart of America and announced that the freaks and misfits and others who chose a life outside of the lines weren’t going to hide anymore, and this was not a small thing.

It makes sense that Chicago is his city, because Chicago is an underdog town. It’s a megacity, but it doesn’t have the sophistication of New York or the glamor of Los Angeles. It’s not San Francisco, the fabulous white city on her eleven mystic hills; it doesn’t have the voodoo jazz-magic of New Orleans. Chicago is Hog Butcher for the World; loving it is like loving a woman with a broken nose. It is a stormy, husky, brawling city that might write you a poem or drop the f-bomb. It is Fitzpatrick’s home, and in his art, he makes it larger than life. He makes it mythical.

I first discovered Tony Fitzpatrick’s work at the Messages & Magic: 100 Years of Collage and Assemblage in American Art exhibit at the Kohler Arts Center in January 2009. I fell in love with his work because of the monsters and matchbooks, tattoo imagery and poetry and pin-up girls—and because of Chicago. For me, much like for Fitzpatrick, it all comes back to Chicago. Though I only lived in Chicago for a handful of years, I spent a lot of time there both before I moved there and after I left. And the time in which I resided there was my late teens and early-mid twenties—the era of my life when I was coming into my own, and developing many of the interests and obsessions which continue to drive me. I think often of something Luc Sante wrote in the introduction to Low Life: Lures & Snares of Old New York. In it, he speaks of his feelings about New York City, and it perfectly describes how I feel about Chicago: I wasn’t born… [there] …and I may never live there again…but I was changed forever by it, my imagination is manacled to it, and I wear its mark the way you wear a scar. Whatever happens, whether I like it or not,… [it] …is fated always to remain my home.

All of Fitzpatrick’s art speaks to me, but none more so than his Chicago pieces. This was as true while viewing Jesus of Western Avenue as it has ever been. I spent a lot of my visit to the CCMA noticing the neighborhoods, buildings, and signage depicted in various pieces—whether they were the focal image or appeared as smaller details—and quietly exclaiming: “Hey! I used to live right near there! I used to work in that building! I hung out at that place all the time!” And it was two of the pieces with signage as the focal point which resonated with me most strongly. Not only because of the visuals, but because of the poetry.

In the piece featuring the DriveOut Auto sign, Fitzpatrick’s words could have come straight from a Lou Reed song, or a Tom Waits song, or from a poet onstage at the Green Mill, performing with a backing jazz ensemble: Cowboys got off horses for a metallic-flake / midnight-blue Impala / with spinning rims and the homicidal snarl of a 386 trying on: steel, / Lord have mercy: steel. / Sequential lights—blinking the Western Avenue semaphore: The Midnight Auto. Open All Nite. / No Money Down.

In the piece featuring the sign for Barry’s Cut Rate Drugs, the poem jumped straight from the streets of Nelson Algren’s Chicago and into the present day: The wind knifed his face like a thousand tiny icicles; he felt his pocket, in a panic, to make sure his wake-up dope was still there… Down Milwaukee Avenue; he saw orange embers dance upward from a garbage-fire like petals from a dragon’s mouth… And for the first time in his life, he sang… And I stood there weeping in front of it; witnessing this small moment of dignity and beauty blossoming before me.

In his essay “The Triggering Town,” Richard Hugo states: The poem is always in your hometown, but you have a better chance of finding it in another. The reason for that, I believe, is that the stable set of knowns that the poem needs to anchor on is less stable at home than in the town you’ve just seen for the first time. He goes on to discuss the concept of setting a poem in either an imaginary town, or one you’ve heard of but never visited, or one you’ve visited but don’t know much about. This town must feel like it is your own, but you will better be able to write (about) it than if you were trying to describe your real hometown, because: …if you need knowns that the town does not provide, no trivial concerns such as loyalty to truth, a nagging consideration had you stayed home, stand in the way of your introducing them as needed by the poem.

In Tony Fitzpatrick’s Chicago-inspired art and poetry, he manages something that most writers and artists—Richard Hugo included, if “The Triggering Town” is any indication—have a hard time achieving. He represents the knowns of the city, the very real people and places, but also doesn’t feel such a loyalty to ‘truth’ that he neglects to include the imagined knowns of his triggering town. That is—he’s not so hung up on the facts of Chicago that he shies away from representing the deeper truths of how Chicago feels. In Fitzpatrick’s Chicago, the Heart ‘O’ Chicago Motel can coexist with the mermaids in Lake Michigan, and a Dracula parrot can appear in Humboldt Park. Justin Witte, curator of the Cleve Carney Museum of Art, compares the layers of Fitzpatrick’s collages to the layers of the city. He layers the myths on top of the realities, and vice versa.

In a recent interview, Fitzpatrick said: “I wake up sometimes enraged at the thoughtless cruelty—and make no mistake, Chicago is a profoundly cruel place. At the absolute rampant racism—the way people of color are treated by the police, I just find it endlessly lamentable. The classism—the idea that the fellow citizen is succeeding at your expense—that’s a small, sociopathic place to be. And other mornings I’ll wake up and just realize the place is luminous and shot through with poetry and grace.” In his art, he simultaneously portrays the thoughtless cruelty and the poetry and grace, and he shows us the stable knowns of the city as-it-is alongside the invented but emotionally resonant “knowns” of an imagined Chicago.

To see Jesus of Western Avenue is to enter Tony Fitzpatrick’s Chicago—Tony Fitzpatrick’s world. It is to visit his triggering town—a place populated by underdogs and mythical beasts; where the birds adorn their feathers with stars and planets and the moth-girls jazz above the buildings flinging magnetic curses, stringing poetry and f-bombs onto necklaces of charms. A cruel, luminous city where the junkies sing, and night is another country.

ENDNOTES

Jesus of Western Avenue will be at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art through January 31, 2022. Tickets are free, but you have to reserve a date and time slot.

If you want to get a bite to eat while you’re in Glen Ellyn, check out Sushi Ukai. Their food is amazing (the ponzu sauce they serve with their gyoza is some of the best I’ve ever had), and they have a kitty-cat robot waiter named Bella. Also, I’ve heard it’s where Tony Fitzpatrick himself often eats when he’s in town—and right around the corner from the restaurant, there is a wall featuring two of his collages enlarged to mural size.